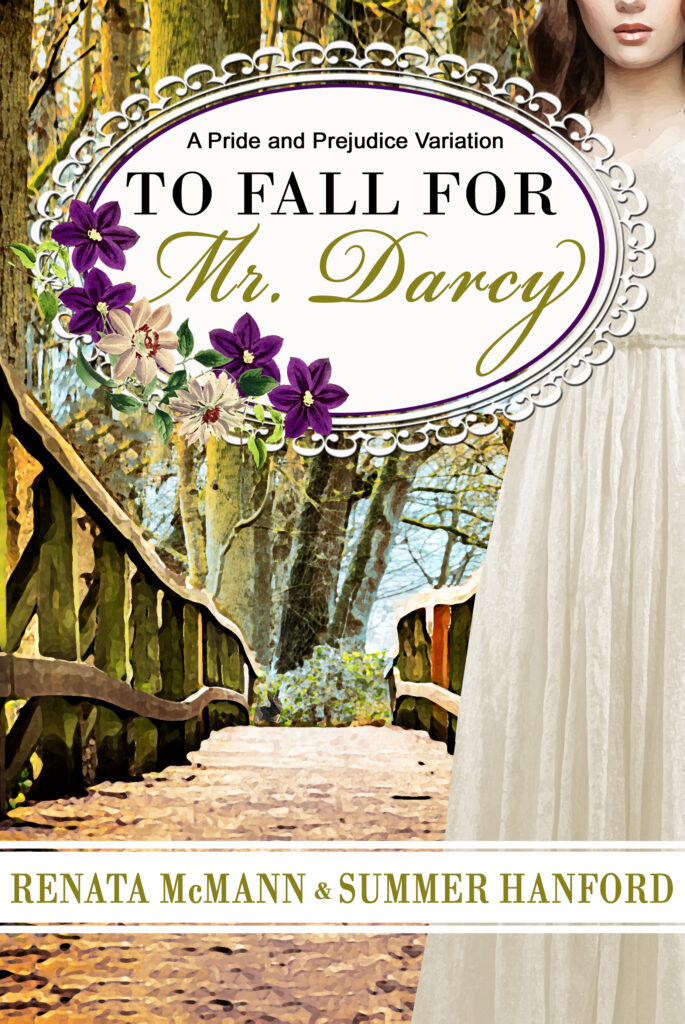

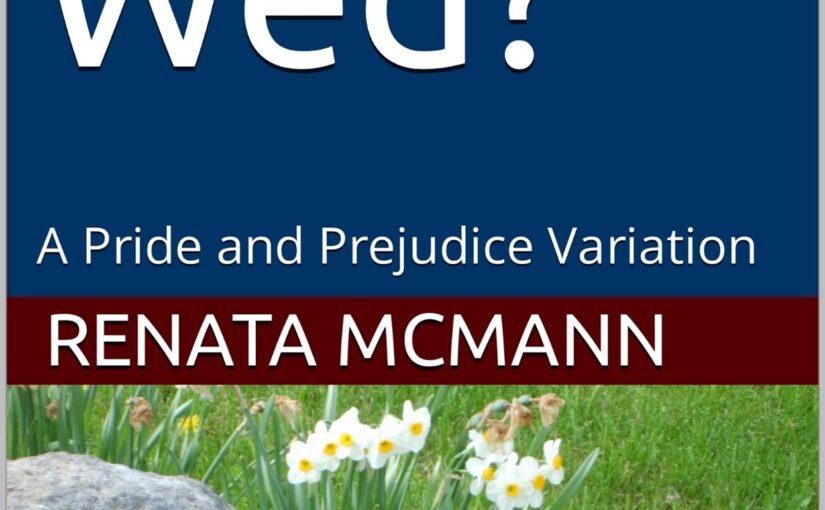

by Renata McMann and Summer Hanford

Mr. Collins was a fool, yes, but not a fool who deserved to die.

Torn between anger with her cousin and remorse on his behalf, Miss Elizabeth Bennet must navigate the changes Mr. Collins’ demise brings to her family and sort out her feelings for both the charming Mr. Wickham and not-so-charming Mr. Darcy. In addition, she must discover the reasons behind a rash of anger directed her way. But most of all, she needs to learn what, if any, impact will befall her because of Mr. Collins’ Will.

Fitzwilliam Darcy knows he, his family, and his friends are all too good for the likes of the Bennets. Or are they? Decades old secrets and impulsive, and not so impulsive, proposals start reordering Darcy’s view of the world. Will he come to terms with what truly defines a person’s worth in time to claim the woman he loves, or lose her to a charming man seeking a fortune?

Mr. Collins’ Will is a Pride and Prejudice Variation of approximately 100,000 words.

Chapter One

The Netherfield ball, certain to be dubbed the event of the year in their corner of Hertfordshire, stuttered to a slow and agonizing end, none too soon for Elizabeth Bennet. More aggravated than tired, she climbed into the second of the carriages employed by the Bennet family that evening, along with her mother, youngest sister Lydia, and their cousin Mr. Collins. Seated beside her cousin, Elizabeth very much wished she’d squeezed into the first carriage with her father and other three sisters: Jane, Mary and Kitty. The way Mr. Collins gazed at her, his fawning expression illuminated by the lanterns lining Netherfield Park’s drive, turned Elizabeth’s stomach.

The carriage rolled forward, her mother’s voice filling the interior with a babbled recounting of all that had transpired that evening, as if no one else in the carriage had been present to observe the goings on. Fortunately, Elizabeth was so accustomed to Mrs. Bennet’s voice that she could readily ignore it in favor of the thoughts swirling in her head.

Much of the evening had been a disaster. The man Elizabeth had most wished to dance with, her new acquaintance Mr. Wickham, had made no appearance. Mr. Bingley had invited all the officers from the militia recently stationed in Meryton, and all but Mr. Wickham had come. He’d excused himself to London, with no real word of why or when he might return.

But Elizabeth knew why. Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy. That self-important gentleman despised Mr. Wickham to the point that he’d even denied the man a living left him by Mr. Darcy’s father, in some quibble over the exact wording of the will and in complete disregard to the deceased man’s wishes. Mr. Darcy treated Mr. Wickham with even more disdain than he showed the rest of those he felt beneath him, a designation he applied liberally in Hertfordshire insofar as Elizabeth could tell.

It was to avoid Mr. Darcy’s glowers that Mr. Wickham had remained away from the ball. Elizabeth, who fancied she could become smitten with the handsome and charming Mr. Wickham, had planned to converse and dance with him to an almost inappropriate extent. She greatly resented Mr. Darcy’s interference.

Perhaps worse, Mr. Darcy had danced with her, forcing conviviality for the object of her pique. A whole set, spent in mingled boredom and agony. They’d all but quarreled and had found no bridge for enjoyable conversation. At least Mr. Darcy cut a comely figure and danced well. She could say that for him.

Unlike Elizabeth’s cousin, who still gazed at her adoringly. Mr. Collins had danced with Elizabeth so poorly as to cause acute embarrassment and had then insisted on remaining by her side much of the evening. Adding to that her mother’s rant about Jane’s marital prospects with the host of the ball, Mr. Darcy’s friend Mr. Bingley, her sister Mary’s atrocious singing, Miss Bingley’s snide remarks, and Mr. Bennet’s choice to seek amusement rather than curtail any poor behavior by his family members, all meant Elizabeth had trouble finding much enjoyment in the evening. If not for some amusing exchanges with her dear friend Charlotte Lucas, and Mr. Darcy dancing well, not a single bright spot would exist in Elizabeth’s memory of the ball.

She let out a sigh as they continued to jounce down the long drive. They passed another lantern, the light once again illuminating Mr. Collins’ foolish, besotted look. Elizabeth angled firmly to stare out the window, even as they turned from Netherfield Park’s drive and onto the roadway, devoid of any light but the carriage lanterns. She didn’t care if she could see any of the scenery, so long as she didn’t have to witness her cousin’s stares. With her mother babbling on and the weight of Mr. Collins’ regard, Elizabeth deemed it a thoroughly miserable carriage ride.

Finally, they reached their own home of Longbourn, their drive noticeably shorter and less well-lit than Netherfield’s. The comparison aggravated Elizabeth as she recalled the horror on Mr. Darcy’s face when he contemplated the idea of her sister Jane wedding Mr. Bingley. Unfortunately, an equally infuriating disdain had contorted the features of Mr. Bingley’s sisters, Miss Caroline Bingley and Mrs. Hurst, at the notion. It seemed Jane’s cause would find no champions among Mr. Bingley’s friends and relations. With their wealth and connections, they thought themselves so above Elizabeth’s family, it was a wonder they could see Jane, they were forced to look so far down.

Elizabeth permitted a scowl, her face still averted from her companions. If the Bennets were crass and uncouth, Mr. Darcy, Miss Bingley, and Mrs. Hurst were equally ill mannered in their pomposity and condescension.

The carriage rolled to a halt before the front steps and Elizabeth realized that at some point during the drive, her mother had switched from chattering to sleeping. Lydia, the youngest of Elizabeth’s sisters at only fifteen, rested her head on their mother’s shoulder and snored. Mr. Bennet, Jane, Mary, and Kitty headed inside, their carriage having already arrived.

Elizabeth reached across the carriage to shake her sister’s shoulder. “Lydia, we’re home. Wake up.”

“Home?” Lydia mumbled with a yawn. She stretched, unwittingly punching their mother lightly on the shoulder.

“What?” Mrs. Bennet asked, head snapping up.

“I am so sorry to wake you both,” Mr. Collins said, though he hadn’t done so.

He turned to Elizabeth, his eyes wide and his face so foolish that she attempted to recall how much she’d seen him imbibe that evening. Of course, his face was normally somewhat foolish. Maybe it took little alcohol to exaggerate that.

In what she assumed he meant to be sotto voce, he continued, “With them both asleep, you do realize we were hardly chaperoned?” He offered a grin, lopsided with drunkenness rather than intent.

Lydia giggled, her amusement breaking off into another yawn.

The door beside Mr. Collins opened and one of their footmen, Edward, handed Mrs. Bennet down. Lydia scrambled out after her, snickering. Mr. Collins, seated between Elizabeth and the waiting footman, accepted Edward’s assistance next, and would have tumbled face first into the yard without the footman’s strong arm. Shaking off the footman’s support, Mr. Collins turned back, swaying, and extended a hand to Elizabeth.

“I do apologize for disembarking before you, dear cousin,” he said as she reluctantly placed a gloved hand in his. Locking eyes with her, he squeezed her hand.

Elizabeth stepped free of the carriage, rented for the occasion to augment the family’s single conveyance, and yanked her hand from Mr. Collins’ over-tight clasp. “I fail to see how you could have done otherwise, sir.” She nearly added, ‘without me climbing over you’ but the disturbing heat in his gaze curtailed the words.

She hurried to come abreast of her youngest sister and mother, where the latter leaned on the arm of the former. Edward, Elizabeth suspected, would trail behind to ensure Mr. Collins didn’t end up an ignominious heap in the yard. Elizabeth wished the footman were less conscientious.

“Lydia, you’ll see me up, won’t you?” Mrs. Bennet asked. “I’m too tired for the stairs on my own. Oh, what an evening, but it has left me exhausted. What dreams I shall have. Mr. Bingley and Jane wedded. What a fine evening.”

“Yes, Mama,” Lydia said, for once too exhausted for more than simple compliance.

All her sisters except Jane were tired, Elizabeth realized as she joined them in the entrance hall. Lost in a world of her own, if Jane’s dreamy expression were any clue, she seemed blind to the rest of them as she tugged off her gloves, pulling on one finger at a time. Elizabeth smiled, some of her ire over the events of the evening dispersing in the glow of Jane’s happiness.

“Mr. Bennet, a word,” Mr. Collins called as he stumbled through the front door.

Mr. Bennet, who’d been about to head up for the night, turned back. Kitty and Mary skirted him and went up the stairs, Jane following.

“Yes, Mr. Collins?” Mr. Bennet asked and stepped aside to make room for Mrs. Bennet and Lydia to pass.

Elizabeth wished she could join her mother and sisters, but she had a horrible suspicion what Mr. Collins might ask her father and wanted to be there to put a swift end to any such talk. Edward came in behind Mr. Collins and quietly closed the door.

Mr. Collins, who’d been staring at Elizabeth again with that obnoxious smitten look, tipped his head up and sniffed. He sniffed again and scowled. “Wasteful.”

Elizabeth blinked. That was not what she’d expected her cousin to say.

“What is wasteful?” Mr. Bennet asked.

Mr. Collins swiveled around to point at Edward. “He had a fire in the fireplace.” Mr. Collins barreled up to Elizabeth, who adroitly stepped aside, and then passed her, into the front parlor. “This room is too warm,” he cried. “Do you see this, Mr. Bennet? Servants should not waste valuable firewood.”

Elizabeth’s father cast her an amused look. “It’s not wasted. I appreciate coming home to a house that is warmer than the outside.”

“But there are coals in the fireplace,” Mr. Collins called from inside the parlor. A glance showed that he’d fallen to his knees before the grate. “At the very least, they should be taken to someone’s bed chamber.”

“We’re all too tired for that,” Mr. Bennet said. “I’ll be in bed, asleep, before any coals would have the time to heat my room. I daresay my lady wife and daughters will be as well.”

“A waste,” Mr. Collins muttered at the coals. “Squandering. Lady Catherine would not approve. Not at all.”

“Sir?” Edward asked, worried.

Mr. Bennet shook his head. “Don’t give it another thought, Edward. You’ve every right to be warm.”

“Should I see Mr. Collins to bed, sir?”

Expression amused, Mr. Bennet shrugged. “You may make the attempt, but I suspect he’ll only argue with you. It was good of you to wait up. The warm entrance hall is appreciated.”

“Thank you, sir.” Edward bowed and went into the parlor. “Mr. Collins, do you require any assistance, sir?”

“Shall we?” Mr. Bennet asked Elizabeth, gesturing to the staircase as Mr. Collins voice rose in slurred command.

She nodded and headed up the steps at her father’s side.

In a quiet, kind voice, he said, “Do not worry. I know you don’t want to marry Mr. Collins and I won’t push you to do so. Your mother will try to, but I want you to be happy.”

Relief washed through her. In an equally quiet voice, she replied, “I’ve been trying to keep him from proposing.”

Below, Mr. Collins’ voice cried, “So wasteful. When I’m master here, things like this will not be permitted.”

“I don’t think a herd of horses could prevent your cousin from asking for your hand,” Mr. Bennet said, full of mischief. “Your Uncle Phillips took me aside this evening to tell me that Mr. Collins commissioned his help to write a will in your favor. Mr. Collins is convinced you will marry him.”

Elizabeth pursed her lips. “It is unfortunate that he will have to write another will soon.”

Edward’s voice carried from below saying, “Mr. Collins, let me help you. I don’t think the shovel is the best tool to carry hot coals.”

“I can do it,” Mr. Collins said with petulant impatience.

They reached the top hall and Elizabeth turned to go to her room, hoping Mr. Collins would give up conserving coals and go to sleep so she didn’t have to hear his voice anymore that evening.

A loud thump sounded below, accompanied by banging and the clatter of smaller items.

Elizabeth turned back to find her father had, as well. They faced each other across the head of the staircase, uncertain. She opened her mouth to suggest they go back down. Poor Edward shouldn’t be forced to deal with a completely unreasonable Mr. Collins alone.

“Fire,” Edward cried.

“Get water,” Mr. Collins yelled.

“Papa?” Elizabeth gasped.

“I’m sure it will be quickly extinguished, but I’ll get your mother and sisters. You get the servants. I want everyone outside where it’s safe.”

“Mr. Collins, sir, please, stop that. It won’t work,” Edward pleaded below.

“I said get water,” Mr. Collins bellowed.

“Go,” her father ordered.

Worried, Elizabeth grabbed handfuls of her skirt to free up her legs and raced down the hall to the servants’ stair. She looked back once to see her father at her mother’s door. Elizabeth plunged into the dark stairwell, heading upward. Their servants slept under the eaves, above the family’s rooms. A terrible place to be caught if the fire did get out of control.

Stumbling in the low, pitch black attic hall, Elizabeth called, “Wake up. Wake up. There’s a fire. Come out.” She found the first door and opened it. This was not the time for politeness or respect for privacy. “Fire,” she yelled. “Grab something warm but don’t take the time to dress.”

“Do I have time to take my things?” the voice of Betty, one of the maids, asked. There came a clatter and a spark, and a flame bloomed into life at the top of a stub of a candle.

“Not more than two minutes,” Elizabeth guessed. “Hurry, we must rouse the others.”

Betty rushed to the doorway and yelled ‘fire’ several times, louder than Elizabeth had. She pressed the candle into Elizabeth’s hand as one of the footmen came out of his room, then Betty went back in to pull the blanket off her bed. She started throwing shoes and clothing onto the blanket.

Servants spilled from the little rooms, too fast for Elizabeth to be certain she spotted everyone. Betty rushed down the steps with her makeshift bag. Candle in hand, Elizabeth checked each room. Everyone was moving except one of the kitchen maids, who somehow still slept.

Elizabeth went in and shook the girl, who finally blinked her eyes open.

“Fire. Get up.”

“Fire?” the girl slurred, alcohol on her breath.

Elizabeth wrinkled her nose. The cook must have left the sherry out again, and with the family at the ball, it would have been too tempting. “Fire,” Elizabeth reiterated.

With a startled squeak, the maid sat up and jumped from bed. She bolted past Elizabeth without taking anything with her.

Satisfied all the servants’ rooms were empty, Elizabeth rushed back down the narrow steps to the family’s floor. The doors she could see stood open. Thick smoke flowing up the staircase cut off any view of the other half of the upper corridor, where her and Jane’s room stood. Surely, though, her father had finished the task of ordering her mother and sisters out.

Elizabeth plunged back into the servants’ stairwell to follow the staff down. She nearly tripped and tumbled down the steps as something brushed against her legs. Catching the wall with her free hand, she spotted the kitchen’s tabby cat and scooped it up. Clutching the cat close, she clattered down the steps. They came out in the kitchen, the large pots scattered and water sloshed on the floor. The servants she’d roused were already pressing through the garden door, out into the night. Elizabeth followed, then rushed around the outside of the house, needing to see her family.

She rounded the building to find her parents and sisters all standing before the house, staring at flames that filled the front entrance and windows. Elizabeth gasped, staggering to a halt. She dropped the struggling tabby, then fell to her knees in the drive, too relieved and horrified to move.

Her father held his cashbox with a pile of ledgers at his feet. Beside him, Lydia, tears streaming down her cheeks, held a heap of clothing topped with ribbons and hats, and beyond her Mary clutched a jumble of sheet music, books and garments. Kitty and Jane knelt on the ground on either side of Mrs. Bennet, who seemed to have collapsed, gowns in heaps around them. Mr. Collins was nowhere to be seen.

“Elizabeth?” her father called. “The staff?”

Elizabeth struggled up to stand. She stumbled as she crossed the drive, unable to tear her attention from the malevolently glowing, violently thrashing flames to watch where she placed her feet. When she reached her family, Lydia let out a sob, dropped her gowns, ribbons and hats, and threw her arms about Elizabeth.

“The staff?” Mr. Bennet repeated urgently.

“They’re out of the attic. I think they all made it except…” Elizabeth trailed off, watching the flames. “Is Edward in there?”

Mr. Bennet shook his head, grim. The servants Elizabeth had roused trickled around the side of the building. Some came to stand with the family, others rushing about, looking for buckets. Elizabeth bit her lip, unable to voice her worry for Edward and Mr. Collins. She stroked Lydia’s hair. Her youngest sister continued to cry.

Edward stumbled around the corner of the house, soot coated, his eyes wide and over white against the charcoal smeared on his face. Sighting them, he rushed across the yard. “Did he ever come out? Mr. Collins, sir, did he ever come out?”

Mr. Bennet shook his head. “What happened?”

“I tried to stop him. I truly did, but he put the coals on a shovel and was going to carry them to his room. Then he fell and coals went everywhere. He started using a cushion to smother the fire. He moved to another coal and did it again, only the first coal flared up again and caught the carpet. I ran to get water again and again, Mr. Bennet. He kept trying to smother them, but neither of us realized that there was a coal near the curtains.” Edward let out a sob. “We might have been able to put that one out, but there were so many small fires as well. I tried to drag him out of the parlor, but he wouldn’t come with me. He kept apologizing and saying he wouldn’t let the house burn down.” Edward twisted his hands together, knuckles so white it showed through the soot. “I tried to get him to come with me, Mr. Bennet. I tried until I could hardly breathe, but he wouldn’t come.” Tears cut clear tracks down Edward’s cheeks.

“You aren’t to blame, Edward.”

“If only I hadn’t had a fire,” Edward moaned, wringing his hands harder.

“You aren’t to blame, Edward,” Elizabeth repeated firmly.

“Our fool of a cousin is,” Mary added, blinking rapidly.

Mr. Bennet drafted Edward to carry his ledgers and went to the cluster of servants to make sure everyone got out. Sir William Lucas arrived, along with his older two sons. Mr. Bennet went to meet them, still clutching his cashbox.

Mr. Bennet and Sir William organized a brigade to bring buckets of water from the back well to the front of the house. More neighbors arrived. Elizabeth wrapped her mother in a shawl from her pile of clothing, then led her to one of the benches in the rose garden. When her mother was settled, Elizabeth joined Jane and Mary in the bucket line, but it became increasingly obvious that the house would not survive. Soon, the fire was too hot to get near enough for the water to be effective. The bucket brigade became an attempt to keep the fire from spreading.

It was still dark when they gave up. Mr. Bennet sat next to Mrs. Bennet with his cashbox by his side and his most current ledger in his lap. Using the light from a lantern brought by a neighbor to see, he paid each member of the household staff their full quarter’s wages, recording it with a pencil that had been stuck in one of the ledgers. It was a month early, but he added enough money for them to spend a night in the inn in Meryton and get a meal. Probably none would go there, since most had family in the area and others would be taken in for a few days by local people, but he wanted to be sure they all had somewhere to go. Mr. Bennet assured the coachmen, grooms, and farm workers that their work would go on unchanged, as none of the outbuildings had caught fire.

Elizabeth watched the staff take the money with tears in their eyes. They knew as well as her father that he wouldn’t be able to hire them all back for some time, if ever.

By dawn, nothing remained of Elizabeth’s home but a charred, crumpled shell. The Lucas carriage arrived and took her mother and three youngest sisters to their Aunt and Uncle Phillips, in Meryton. Mr. Bennet, Jane and Elizabeth walked the short distance to Lucas Lodge. As she’d been unable to save any of her possessions, Elizabeth took half of Jane’s load. A miserable, soot coated Edward sniffled as he carried Mr. Bennet’s account books but answered in the affirmative when Elizabeth asked him if he would be staying with his parents.

When they came in sight of Lucas Lodge, Elizabeth looked back, expecting to see smoke with the early morning light, but there was none. Whatever whisps were left weren’t visible, although everything smelled of soot and fire. Her hands felt as if they were made of ice, but the remainder of her was numb.

“Poor Mr. Collins,” Jane murmured as they reached the entrance.

Elizabeth nodded, the movement shaky. He’d never come out. The last anyone had seen or heard of him was his apology to Edward. Much as she didn’t care for her cousin, tears slid down Elizabeth’s cheeks. Mr. Collins was a fool, yes, but not a fool who’d deserved to die.